For the love of the game

Being a student-athlete is difficult. From early morning lifting sessions to late night practices, student-athletes face an additional emotional, mental and physical toll on top of being a full-time student. But for many, the love of the game eclipses all challenges. This is especially true for senior athletes Adam Hopkins and Andrew Donnellon who have defied all odds, even dire medical diagnoses, through their love for the game.

A Tin Man with an Iron Will

Andrew Donnellon plays for himself. “Football is the most fun I’ve had playing a sport.” He plays for his team. “It’s a brotherhood. There’s a mutual respect for each other because we put in so many hours of work, in season and off season.” And he plays for the kids in the Pediatric Heart Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. “It gives them a glimmer of hope in a scary situation.”

Donnellon, a sport and recreation leadership major and kicker for Bluffton football was born with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. HLHS is one of the most complex cardiac defects in which the left ventricle, the larger of the heart’s two ventricles, is so underdeveloped it is unable to function and is virtually non-existent. This creates a situation where the left side of the heart is completely unable to support the oxygen-rich circulation needed by the body’s organs.

It’s a complicated diagnosis, but Donnellon typically tells people he has half of a heart.

Because of that, friends in high school nicknamed him Tinman (after the character from “The Wizard of Oz”). Then the Cincinnati Enquirer ran a front page story about him titled, “The Tin Man with an Iron Will.” The name stuck and now even his mom and other family members call him that more often than not. The title bestowed upon him is apt; by the time Donnellon was four, he had undergone three open-heart surgeries to enable his heart to function with just the right ventricle. The series of surgeries is still being perfected, but without them, babies pass away shortly after birth.

“I’m one of the oldest people with this condition. There are a lot of variables. The statistics online are treacherous. They’re scary,” said Donnellon, who often meets with expectant parents of children with the same condition.

“I feel like it’s my obligation because I’ve been blessed with the good fortune to make it to 22 years old. I’m one of the best examples you can find. It makes me appreciate and wonder why, but at the same time, I just try to help people. It’s my life calling. It’s what I’ve always done. It’s what I should do.”

Complications could arise, but Donnellon monitors his health through monthly blood tests and check ups at the adult wing of Cincinnati Children’s twice a year. The journey isn’t always easy to say the least, but Donnellon says that staying positive is his only option.

Beyond the Barriers

Donnellon’s parents were given dire information about the prospects and limitations

their little boy faced. They were told that, even if the surgeries were successful

and he survived, he wouldn’t be able to play sports or keep up with his friends. But

in the first grade, with all of his other friends playing soccer, his parents allowed

him to join the team

“I always knew I had a heart problem, but my parents never made it apparent that it

was life or death. The way I was raised, I was just a normal kid who got out of breath

more quickly than others, but as I grew up I somehow was able to keep up with or excel

past other kids.”

Through the years, Donnellon also picked up baseball and volleyball. He didn’t start

playing football until his junior year of high school when his high school team was

in desperate need of a kicker halfway through the season. As a former soccer player,

he thought he might be a good fit. On a Monday he approached Brian Miller, head coach

at Purcell Marian High School in Cincinnati, who thought he was joking. Donnellon

spent a week convincing the coach, collecting paperwork and passing physicals. By

Friday, he was the team’s starting kicker.

“My doctors wrote on my physicals, ‘Avoid contact if possible.’” With a laugh he added,

“That is generally a good rule.”

Bluffton takes a chance

Donnellon was recruited by several colleges and universities, but as soon as his medical

history was revealed, the calls stopped coming.

“They would back out. They just weren’t interested anymore.”

Then Donnellon attended a camp at Bowling Green State University. A member of Bluffton’s

coaching staff, led by former head coach, Tyson Veidt, was also there.

“Bluffton is the only place that let me play, which meant a lot to me. Coach Veidt

was only here for my freshman year, but he put me on the path to continue playing.

When he left, Coach Dorrell came in and he was just as on board with letting me play.”

Donnellon was the point-after-touchdown kicker for this past season, when the Beavers

went 7-3.

“I’m not concerned at all; everyone is very protective of me,” said Donnellon. “When

I’m on the field, the guys go even harder at it.”

At the beginning of this season, upperclassmen spoke to the incoming freshmen. Donnellon’s

topic—heart.

His commitment to the team is permanently inked on his right arm. The Bluffton “B”

is etched into a tattoo on his forearm that reads, “Be Like Me.” A nod to his cardiothoracic

surgeon, Dr. Roger Mee. This tattoo is alongside tattoos of names, symbols and sayings

that have inspired him and that make him remember just how lucky he is.

“Bluffton has been a big part of my life. Bluffton gave me the opportunity to do the

thing I love.”

Now, the baby who was given a 50-50 chance of surviving past age 5, is the only NCAA

football player to have undergone three open-heart surgeries.

Adam Hopkins calls himself a pretty average player

However, the criminal justice major from Wellington, Ohio, and member of the men’s

basketball team, in reality is pretty remarkable.

“I don’t hold any records. I guess my record is I’m the first guy to play basketball

at Bluffton and beat cancer at the same time.”

Nine games into the 2015-16 season, doctors at the Cleveland Clinic diagnosed Hopkins

with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a cancer of the lymphatic system.

“I was shocked. I was young. I was 21. I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t even

know what it was. Then he said it was cancer. At first, I didn’t know that Hodgkin’s

lymphoma was cancer,” said Hopkins.

The signs

One year earlier, Hopkins noticed a small bump forming on his neck. He shrugged it

off thinking it was a pulled muscle, but he decided it was definitely nothing concerning.

He felt great. But while it remained small, it didn’t go away, and instead, kept growing.

“We even joked on the team, ‘What if this is something serious.’”

In December 2015, he went to an ear, nose and throat specialist in Bluffton. Hopkins

says the doctor put a probe Winter 2017 Bluffton University 17 down his throat, but

the doctor couldn’t see anything abnormal. So Hopkins had an MRI. A mass was located,

and Hopkin’s was told it could be Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but he still didn’t believe

anything was wrong. So he got a second opinion and a biopsy completed at the Cleveland

Clinic. A team and a family

A team and a family

Hopkins got the diagnosis over the weekend, but immediately returned to Bluffton.

Despite concerns from his parents, Hopkins wanted to live his life as normally as

possible and that meant returning to Bluffton and to his team, which he considers

a second family.

“I’ll never forget walking into my room and telling my roommate (Trey Elchert) I have

Hodgkin’s lymphoma and it is cancer, and I was just bawling. He put his arm on my

shoulder, and the first thing he said was, ‘You are going to be alright.’ There was

never a doubt with any of my teammates or any of the people around me that I wouldn’t

be okay.

After the diagnosis, Hopkins was forced to stop playing and practicing basketball,

but he remained a true member of the team. Hopkins continued to work out with the

guys and attended all of the home games, but he moved into a room of his own.

“When you go through chemo your immune system lowers, so the doctors wanted to isolate

me, but I didn’t want to be isolated because I needed to be around my team. I needed

to be around those guys to live a normal life,” said Hopkins. “So I got a room to

myself, but I was close enough to the guys that if I was sick on one day, I could

have my own space, but if I wanted to talk or hang out the guys were just two minutes

away.”

Every other Friday, Hopkins traveled to Cleveland for chemotherapy. He came back to Bluffton on Sunday night.

At times it was grueling, but through the support of faculty, coaches and friends,

Hopkins maintained a full load of classes and remained a presence on the team.

“My role obviously changed. Since I wasn’t practicing, I was seeing the team from

a different angle. I realized what the coach’s perspective was,” said Hopkins. “I

would get on the guys and tell them to step it up. I would critique them. It was all

in good spirits, but they would come right back at me with, ‘You’re not one of us

anymore.’”

Hopkins says this with a smile because getting teased was the ultimate proof that

he was just one of the guys. “They were never soft on me, and that’s what I needed.”

Return to basketball

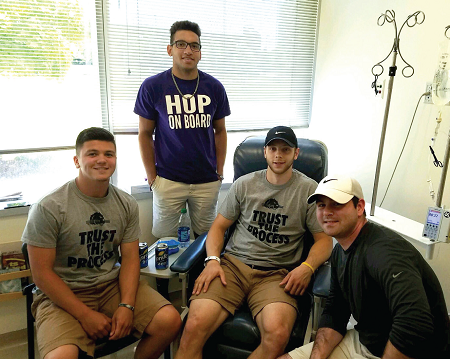

After six months of chemotherapy, Hopkins received his last dose on June 24. “I always

treated treatment days like normal days. I didn’t know anybody was going to show up.”

But they did. Four teammates and three coaches (from both high school and college)

went to the Cleveland Clinic to offer their support and to celebrate.

“I was surprised. They came all that way to watch me sit in a chair and get sick,”

Hopkins chuckled.

Hopkins gets tested every couple of months to see if the cancer has returned, but

so far all tests have come back clear. He’s returned to the court, but perhaps a little

thinner.

“Now, it’s just like I was any other teammate with an injury last season, like a player

with a torn ACL that had to sit out. We treat it the same way.”

But life is different. Hopkins says his faith is stronger and he deeply connects with

Jeremiah 29:11 “For I know the plans I have for you.”

And his relationships are stronger. Whereas Hopkins would have missed his teammates

upon graduation without having cancer, the bond is forever cemented.

“I’m already dreading it,” Hopkins said of graduation and then in a very serious manner,

“I truly believe Bluffton basketball and my teammates saved my life.”

Included Content