The Development of Modern Architecture: |

The Development of Modern Architecture: |

| The skyscraper is the most important development in 20th century architecture. Techniques for making steel, a more refined and stronger iron, led to new possibilities in architecture. Metal beams can span great distances and support increased loads. With steel-cage construction, the exterior no longer has a support function so windows can be larger. Not only structural steel, but new construction methods were necessary for the development of the skyscraper, such as steam shovels, cranes, hydraulic jacks, pile drivers, pneumatic hammers, concrete mixers, and a host of other machines--all in use before World War Two. Timber scaffolding was replaced by stronger tubular steel scaffolding.

Another technical development which made tall buildings feasible was the invention of the elevator, first installed in 1857; the electric elevator dates from about 1889 and by about 1900 the escalator was invented. As early as the late 1920s air-conditioning was used. Gradually new materials were invented: aluminum in windows, stainless steel for sleek interiors, new kinds of glass. It's important to consider why skyscrapers were built. For one, they were a practical necessity: to provide residences, to centralize large commercial enterprizes. A tall building allows for intense occupancy. In addition, the skyscraper is more economical in urban locations where commercial property is expensive.

| ||

MAS MAS |

But the skyscraper also became symbolic. Height became an obsession. Corporations wanted to have the tallest building. Cities also competed in the height sweepstakes. The visibility of the skyscraper signified commercial success; thus, companies often wanted a striking cap or tower--a unique skyline identity. Some today, like the Transamerica Corporation (left), use their office tower as a kind of logo. | |

From the beginning there was one significant problem: with a number of skyscrapers the street-level environment could become a sunless canyon. Eventually, cities passed ordinances requiring a series of setbacks. This proved to be helpful aesthetically since skyscrapers then didn't have to look like a classical columns; instead, they could have shelf-like recessions with roof terraces or penthouses. | ||

|

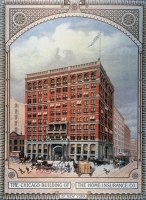

William Le Baron Jenney (1832-1907)This 10-story office building is usually called the first skyscraper. The problem for architects was how to treat the top and bottom of a tall building. A precedent was the Italian palazzo with a clearly defined base and cornice. |

|

Louis Sullivan (1856-1924)Although this 10-story office building uses organic ornament (Louis' stylistic innovation) and still has the sense of a base, shaft, and capital, it has a strong sense of verticality or emphasis on height. |

|

both MAS both MAS |

Burnham and Root | ||

|

MAS MAS |

Although this is technically a skyscraper, it is actually a conventional masonry building. In order to support the 16 stories, the walls at the base are 72 inches thick and the size of window openings had to be restricted. Older styles of construction are pushed to the limits here; in fact, this was the tallest building ever constructed with supporting brick walls. |

Cass Gilbert (1859-34) |

|

both MAS both MAS |

Details in the entrance, the setbacks, and top borrow from Gothic architecture. The Gothic cathedral did in fact provide the outstanding precedent for a tall building. Preachers at time called the Woolworth Building the "Cathedral of Commerce" because of its Gothic details and its 3-story lobby with gold mosaics, one of which depicts Woolworth holding his building, just as medieval paintings depicted the donors of churches offering their works to God. See this site for additional images. | ||

all MAS all MAS |

|

|

|

William Van Alen (1882-1954)Only seven years after the Chicago Tribune competition, this famous skyscraper adopts a different style--Art Deco. It even playfully incorporates hubcaps and hood ornaments as part of the design. The design also makes a virtue of the necessary set backs required by the zoning laws. See this site for additional images.

|

|

| ||

|

|

MAS MAS |

All images marked MAS were photographed on location by Mary Ann Sullivan. All other images were scanned from other sources or downloaded from the World Wide Web; they are posted on this password-protected site for educational purposes, at Bluffton College only, under the "fair use" clause of U.S. copyright law.