The Development of Modern Architecture: |

The Development of Modern Architecture: |

|

|

|

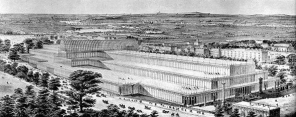

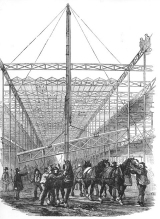

Construction using wrought iron elements based on a 4 foot moduleThe construction of this huge building took about 6 months, which was almost miraculous then and made possible by the use of pre-fabricated modules of cast iron and glass. The building covered 18 acres with almost a million square feet of exhibit space. It had a central nave 72 feet wide and a barrel vault 135 feet high. The interior contained galleries for exhibits from around the world. Unfortunately, given its similarity to a greenhouse, it presented problems of climate control. | |

The Opening of the Great 1851 Exhibition by Queen Victoria; the Transept (strategically placed to cover the tall trees on the site); the foreign exhibition galleries | ||

|

|

|

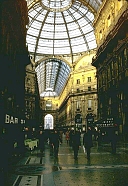

Metal and glass construction became common all over Europe and the United States--for department stores and shopping malls. One of the most famous is the Galleria by Giuseppe Mengoni (1829-77) built between 1865-77 in Milan. Located across the plaza from the Milan Cathedral, it echoes that church in its cruciform plan. It has a skylit "nave" and "transept" with a central dome of glass. | ||

|

|

|

|

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923), an engineer-architect who designed bridges, exhibition buildings with exposed metal work, and even the interior armature for the Statue of Liberty, received the commission for the so-called Eiffel Tower for the Universal Exhibition of 1889. | ||

|

both MAS both MAS |

Built of wrought iron, it is 984 feet tall, the tallest structure in the world until the Empire State Building was erected several decades later. This metal skeletal structure of 15,000 metal parts has both rectilinear and curvilinear ornamentation in iron. (See also this site for additional information and images.) |

Most of the former examples were designed by engineers, not really architects. Metal came to be used for permanent architectural purposes, not just utilitarian structures. | ||

|

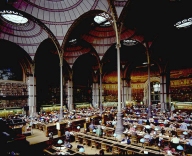

Henri Labrouste (1801-75)The outside of this beautiful library is masonry, but the inside uses the modern, then "high-tech" material, decorative iron work. The ceiling is two barrel-vaults ( a form that goes back to the Romans) with lacy cast iron "ribbing" in a floral pattern. Slender Corinithian columns can be supportive because they are strong metal. The columns are supported on tall concrete pedestals. | |

| ||

|

|

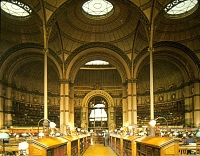

Henri Labrouste (1801-75)The slender columns in this reading room in France's national library (parallel to the Library of Congress) are gracefully designed metal. Skylights complete the effect. Here metal and glass are ART! |

Only with these developments in the use of iron and steel could modern cities have been built. With the development of concrete and later reinforced concrete other kinds of structures were possible. Another invention, the elevator, made multi-storied buildings practical. Click here to continue the story of the development of modern architecture | ||

All images marked MAS were photographed on location by Mary Ann Sullivan. All other images were scanned from other sources or downloaded from the World Wide Web; they are posted on this password-protected site for educational purposes, at Bluffton College only, under the "fair use" clause of U.S. copyright law.